How the fossil group known as the Ediacaran biota relate to modern organisms has long troubled researchers. In a new study, published in Biological Reviews, researchers from Sweden and Spain suggest the Ediacarans reveal previously unexplored pathways of animal evolution. They also propose a new way of looking at the effect the Ediacarans might have had on the evolution of other animals.

The fossil record of animals starts for sure by about 540 million years ago, but animal origins before this point have remained obscure. Darwin himself worried about this problem at length in the “Origin of Species”. After Darwin's time, a famous group of fossils was discovered called the Ediacaran biota, named after a remote mine in South Australia where many were found. They are now known to be widespread from the time just before the animal fossil record starts.

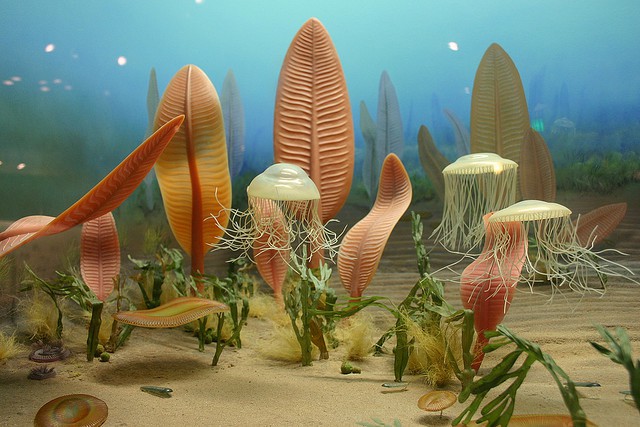

But what are these peculiar organisms? Their strange morphology has made relating them to modern organisms very difficult, with suggestions that they are related to anything from plants, fungi and lichens to recognisable animals such as worms and arthropods.

In a major review of the Ediacaran fossils recently published in Biological Reviews, Graham Budd, professor of palaeobiology in Uppsala University, Sweden, and Sören Jensen, researcher at Badajoz University, Spain, suggest that most of the Ediacarans are very basal representatives of animal lineages, and as such are likely to reveal the hitherto obscure pathways taken by animal evolution. This goes some way to explain why they happen to appear just before clearly recognisable animals do in the fossil record, and raises questions of the ecological relationship between the two biotas.

Traditionally, it has been thought that more advanced animals, many of which are mobile and can burrow energetically through the sediment, were kept in ecological obscurity by the largely immobile Ediacarans, just as the mammals were by the dinosaurs; and it was not until the Ediacarans all went extinct that the mobile animals could diversify in the so-called “Cambrian explosion”.

Budd and Jensen propose a new view of this relationship however, inspired by the interaction between the vegetation and animals in the modern savannah environments of east Africa. In their new 'savannah' hypothesis, they propose that concentration of nutrients both above and below the sediment-water interface were enhanced around the stationary Ediacarans, and the creation of these resource “hot spots” created a very diverse environment, ideal for both diversification and for investment of energy into movement. Rather than the Ediacarans and later animals being direct competitors then, the Ediacarans themselves created a permissive environment that was ideal for higher animals to evolve in.

This idea fits well into a modern view of evolution, called “ecosystem engineering” whereby key species (such as beavers) influence the environment in order to create new evolutionary and diversity opportunities for other species. Perhaps then, the Ediacaran taxa weren't impediments but the drivers of the evolution that eventually led to the rich animal diversity we see today.

Cover image: Life in the Ediacaran Sea (Ryan Somma, Flickr).

References

DOI: 10.1111/brv.12239

Stats

- Recommendations n/a n/a positive of 0 vote(s)

- Views 1566

- Comments 1

Recommended

Post a comment

Comments

-

Robert Kendall Tuesday, 08 December 2015 - 20:20 UTC

It seems to be self-contradictory. First it says the Ediacaran oddballs themselves were abyssal members of the animal lineages, but then they describe the animals as [prospering in various commensal and symbiotic relationships with the Ediacarans.