Trace concentrations of antibiotic, such as those found in sewage outfalls, are enough to enable bacteria to keep antibiotic resistance, new research from the University of York has found. The concentrations are much lower than previously anticipated, and help to explain why antibiotic resistance is so persistent in the environment.

Antibiotic resistance can work in different ways. The research described the different mechanisms of resistance as either selfish or co-operative. A selfish drug resistance only benefits the individual cell with the resistance while a co-operative antibiotic resistance benefits both the resistant cell and surrounding cells whether they are resistant or not.

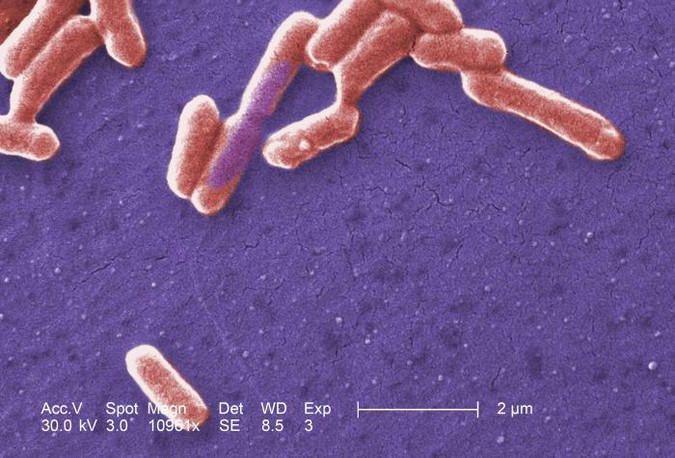

The researchers analysed a plasmid called RK2 in Escherichia coli, a bacterium which can cause infectious diarrhoea. RK2 encodes both co-operative resistance to the antibiotic ampicillin and selfish resistance to another antibiotic, tetracycline. They found that selfish drug resistance is selected for at concentrations of antibiotic around 100-fold lower than would be expected – equivalent to the residues of antibiotics found in contaminated sewage outfalls.

The study, which is published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (AAC), involved Professor Michael Brockhurst, Dr Jamie Wood and PhD student Michael Bottery in the Departments of Biology and Mathematics at York.

Dr Wood said: “The most common way bacteria become resistant to antibiotics is through horizontal gene transfer. Small bits of DNA, called plasmids, contain the resistance and can hop from one bacteria to another. Worse still, plasmids often contain more than one resistance.”

Michael Bottery added: “There is a reservoir of antibiotic resistance out there which bacteria can pick and choose from. What we have found is some of that resistance can exist at much lower concentrations of antibiotic than previously understood.”

This article is a derivative of a public release from the University of York.

Cover image: E. coli (Phil Moyer, Flickr).

References

DOI: 10.1128/AAC.02441-15

Stats

- Recommendations n/a n/a positive of 0 vote(s)

- Views 1084

- Comments 0